By JASMINE BALA

Staff reporter

Threats to press freedom are actually threats to the public’s right to know, says the co-editor of a new book that examines efforts to undermine Canadian journalists’ abilities to do their jobs.

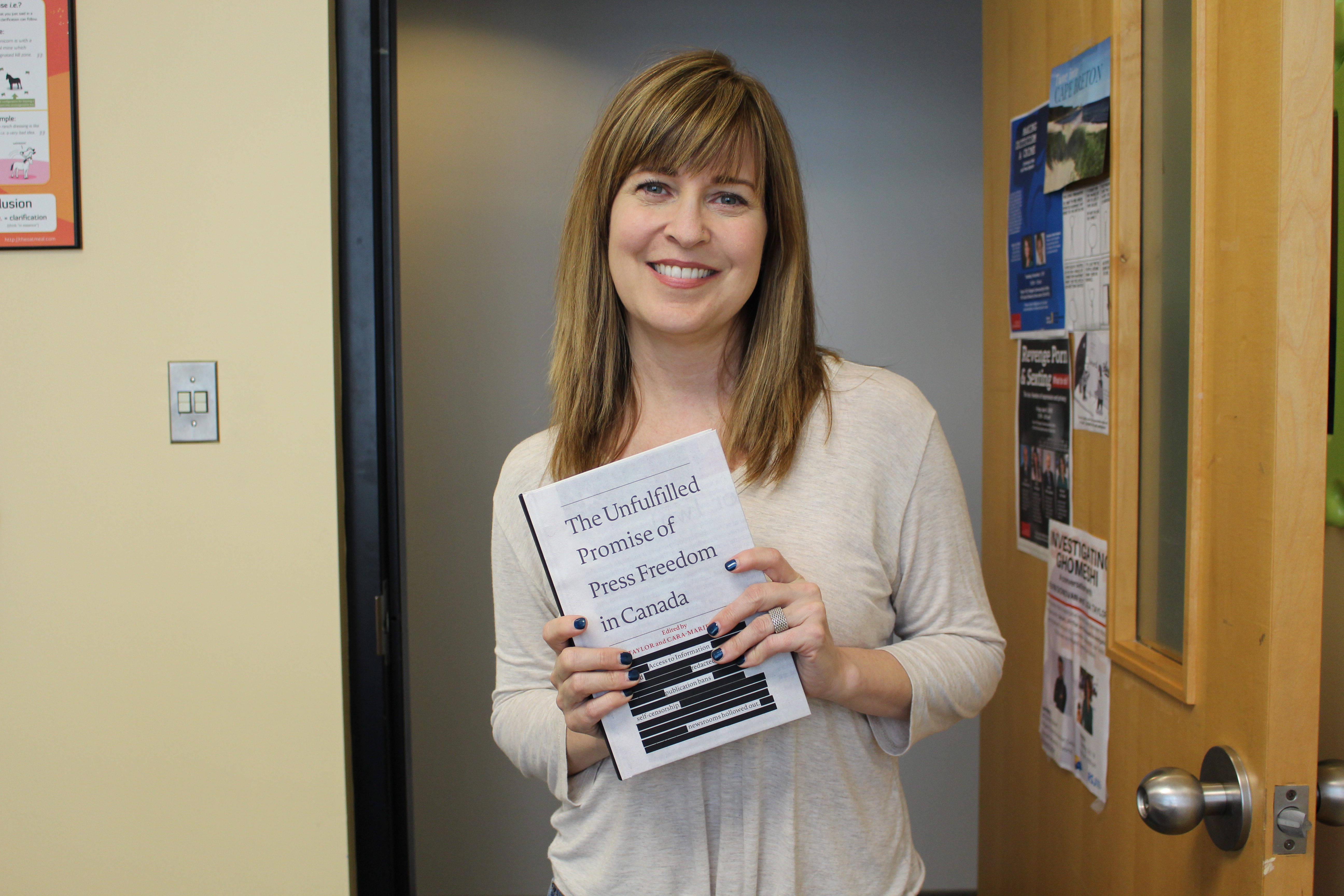

Lisa Taylor, a lawyer, award-winning journalist and assistant professor at the Ryerson School of Journalism (RSJ), said that the discourse surrounding press freedom in recent years is worrisome because it overlooks the real cost of restrictions on journalistic work.

“Journalists don’t seek access to information so that they can just talk to other journalists about it,” Taylor said. “The end game is in sharing it with the public, and I think somewhere along the line we’ve lost sight of the idea that all the media are is a surrogate for the public.

“The public can’t drop everything and go to court for a day. The public can’t make it their job to spend weeks tracking down information and accessing it through Freedom of Information (FOI) requests. Journalists don’t do it to benefit journalists, they do it to benefit the world at large. Press freedom is not really a freedom for the press, it’s a freedom for the people who receive information from the press.”

The Unfulfilled Promise of Press Freedom in Canada, edited by Taylor and Cara-Marie O’Hagan, the former director of the Ryerson Law Research Centre, is a collection of essays by academics, journalists, lawyers and others. The edited volume, Taylor writes in an opening note, explores how press freedom has been constrained by “governmental interference, threats of libel suits and financial constraints.”

Taylor said the chapters examine press freedom “from many different angles,” an approach that makes it different than other books on the topic.

“It was exciting because I think often academics write stuff that only other academics read, or journalists write about this issue and academics don’t bother with what journalists have to say about it,” Taylor explained. “So as someone who has been a journalist, works as an academic and has worked as a lawyer, it was, quite selfishly, really exciting to pull together these three worlds that I’ve inhabited.”

Contributors to the collection include RSJ professors Ivor Shapiro and Gavin Adamson, City of Vaugan integrity commissioner Suzanne Craig, court reporter Robert Koopmans and former CBC media lawyer Daniel Henry. They cover topics ranging from press freedom and privacy in the digital sphere to reporters’ access to information during court proceedings and the press freedom provisions of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Taylor’s own chapter discusses the difficulty of rescinding publication bans on the identity of sexual assault complainants who want their bans lifted. These bans automatically come into effect if either the prosecutor or the complainant ask for it. Not only do the bans prevent media from publishing the identity of complainants, Taylor writes, they also prevent complainants from identifying themselves as sexual assault survivors during and after proceedings. This impedes the complainant’s charter rights under section 2(b), she continues, which states that everyone has the “freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication.”

“What happens is, if we have a willing sexual assault complainant who would like to speak to the press they are prevented from speaking publicly,” Taylor said in an interview. “[This] means that the press is also prevented from disseminating their words. So it’s just another way in which press freedom is hampered.”

Taylor suggests a more flexible approach is required, one that will “ensure that the complainant who wants to have the protection of the statute will still have that opportunity, while the complainant who chooses to speak out will be able to exercise the rights she is guaranteed under the charter.”

The book draws on papers presented during Press Freedom in Canada: A status report on the 30th anniversary of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, a 2012 conference organized by the Ryerson Journalism Research Centre.

When the charter was put into place in 1982, Taylor said, it looked like journalists finally had the guarantees of press freedom they needed. As it turned out, however, that was an overly optimistic assessment.

Before the charter was enacted, “we saw unfair restrictions on the press [and] we saw simple FOI applications take weeks, months or even years to be fulfilled,” Taylor said. “Back when it was first enshrined, there’s no way I could have imagined that in 2017 we’d be fighting a lot of the same battles. It just looked like it was on its way out. There was great promise that came with the charter and we just haven’t seen it fully realized. In fact, we’ve seen some back steps.”