By JASMINE BALA

Staff reporter

Building audience engagement has long been a newsroom preoccupation, only today it involves Instagram and Facebook, while in the past publishers seduced readers with paper cut-out toys and thrilling accounts of reporters on around-the-world races against time.

New research on the history of Sunday newspapers by Paul Moore, an associate professor in Ryerson University’s sociology department, examines one of the greatest audience engagement gimmicks of all time: The New York World’s decision to send reporter Nellie Bly travelling around the globe. Bly was assigned to beat the fictional record described in the Jules Verne novel “Around the World in Eighty Days.” She completed the trip in 72 days.

“There was, of course, a guessing contest for readers to be more personally invested in The World’s regular reports of Bly’s travels,” Moore and Concordia University professor Sandra Gabriele write in their forthcoming book, The Sunday Paper.

They examine Bly’s exploits as part of their research on the history and role of weekend newspapers in mass consumer society between 1888 and 1922 in North America. The research, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, will be published by the University of Illinois Press as part of a larger series, The History of Communication.

The 1890s was a period of innovation and experimentation as publishers tried to attract audiences and teach people “how to read the newspaper when it was a new object – a mass-leisure object,” Moore said. What was happening back then, he explained, is similar to what’s going on today: News organizations faced with massive disruption due to digital technologies are experimenting with “new practices of reading and new practices of engaging with the [news] now that it has a new form.”

Guessing contests were a popular form of audience engagement in the 1890s. In the case of Bly’s travel assignment, readers were asked to guess how many days the trip would take. The winner received a free trip to Europe. Guessing contests, Moore added, almost always required the purchase of a newspaper to obtain a ballot, so the device was “clearly about selling papers. But it’s also about engaging people with the act of buying the paper and with the act of reading the paper closely.”

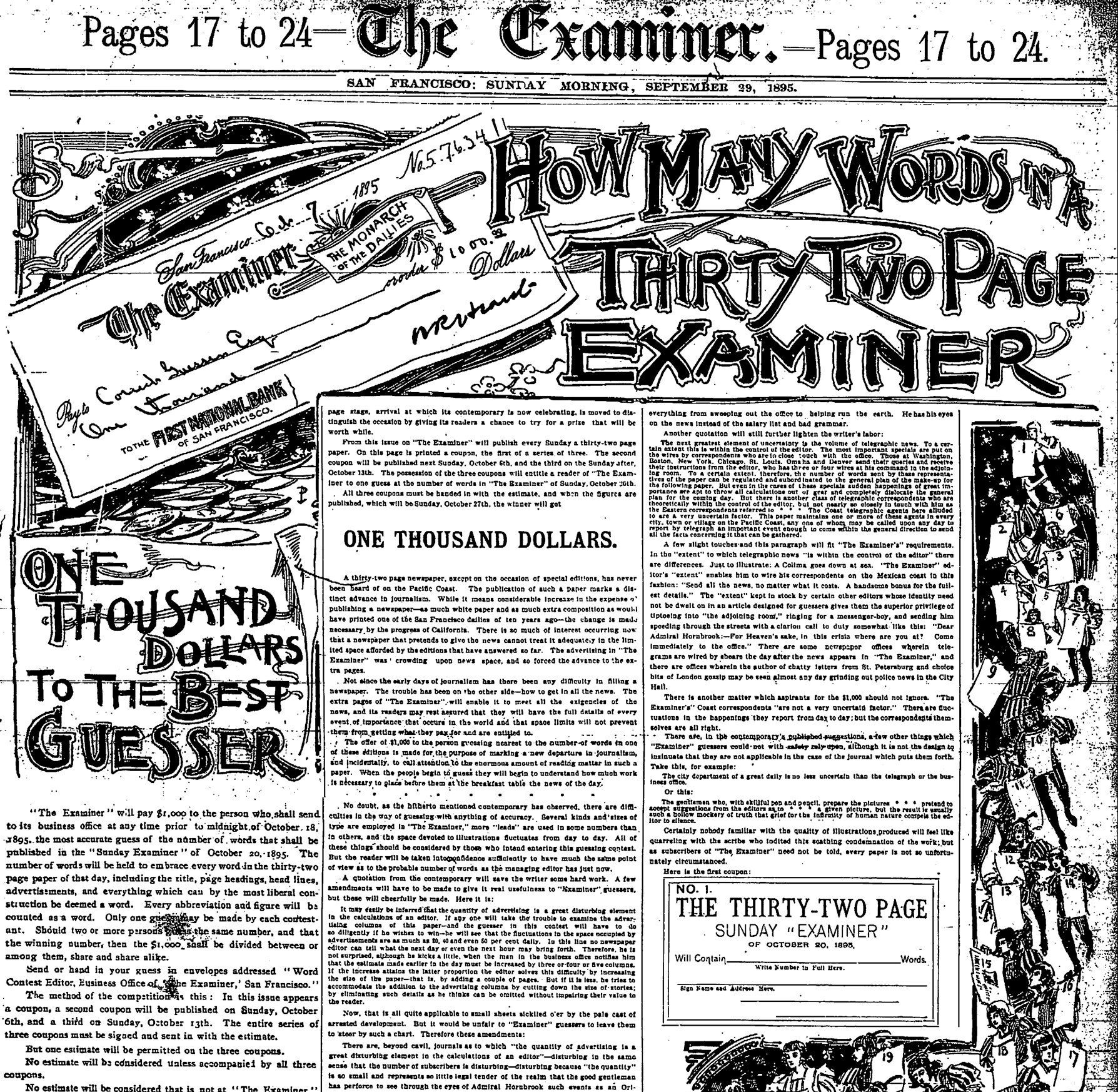

The guessing games usually involved contests more modest than circumnavigations of the globe. In 1895, for instance, both The San Francisco Examiner and the San Francisco Chronicle ran contests asking people to guess the size of their large Sunday editions and offering cash prizes to the winners, Moore and Gabriele wrote.

The publishers asked “how many words [were] in a 32-page Examiner or how many words [were] in a 28-page San Francisco Chronicle…which is just crazy to think of,” Moore said. “But people sent in guesses – educated guesses – and won those contests.”

Advertising, puzzles and photographs in the Sunday paper were other early strategies designed to make reading the paper and engaging with the news a habit. Supplements like paper cut-out toys were included for younger audiences; The Boston Sunday Globe, for example, gave away paper dolls with miniature stage sets.

While the supplements weren’t news, Moore said, “they are as important as the news itself or even more important than the news itself for that role that the historic newspaper had in creating [engagement in] mass society.”

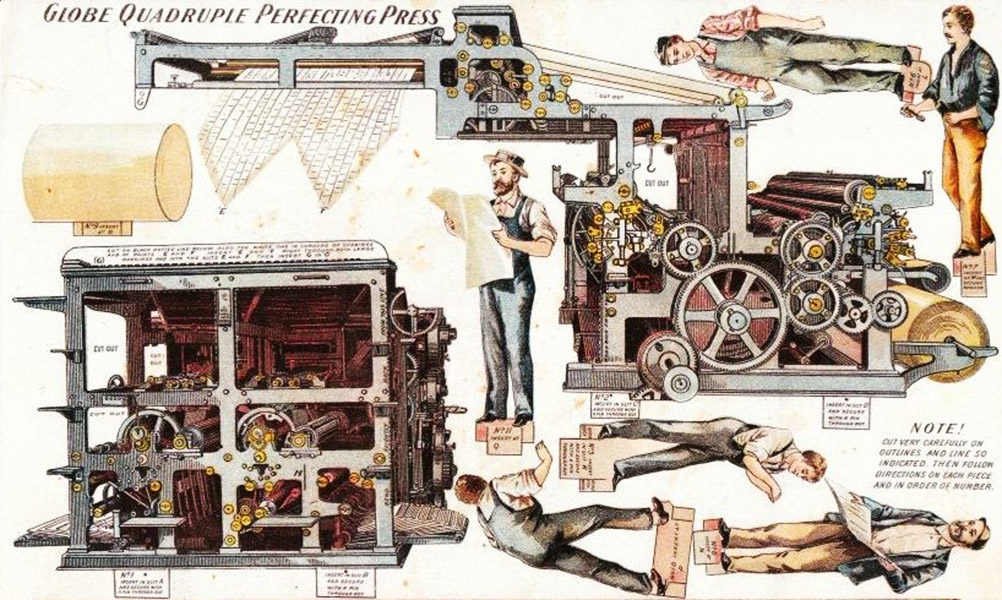

Publishers also built engagement by offering readers behind-the-scene glimpses of how newspapers were produced. The Chicago Herald and The Philadelphia Inquirer did this by installing viewing galleries overlooking pressrooms to show off their new press machines at work, Moore and Gabriele wrote.

While the technologies have changed, the authors argue that variations on the same strategy are still used to engage audiences. These days, for instance, the Chicago Tribune offers opportunities for readers to meet Tribune journalists in person as well as two-hour tours of their printing plants for $25.

Other newsrooms are using virtual reality (VR) tools to provide audience experiences. “They’ll make a New York Times VR documentary about the production of the paper itself,” Moore noted. And when The New York Times Magazine (NYT) published its first virtual reality piece, “The Displaced,” two years ago, it gave all print subscribers a Google Cardboard VR viewer with the weekend paper so they could watch it.

More recently, the magazine created its own Minecraft world as part of a larger feature on the video game. Readers could log onto the NYT server and explore the magazine’s world if they had the game downloaded. A video that showcased the world was available for those who did not have Minecraft.

Historically, Moore said, the Sunday papers touched on all parts of daily life: leisure, business, democratic engagement and shopping. But in the 21st century, he observed, the newspaper for the most part no longer carries the department store ads, movie listings and the classifieds that are all easily accessible online.

“The paper has been left with only the news and not the other sections in the same website,” Moore said. “So, you know, the internet itself, unfortunately for newspapers, is the new Sunday paper in the 21st century…The internet itself is that form that contains all the supplements to the news and that doesn’t hold out hope for traditional news organizations maintaining their commercial dominance.”

Audience Engagement Then

- Contests: Prizes were offered to individuals who won guessing contests on everything from elections outcome and census population counts to the newspaper’s own production statistics.

- Paper cut-out toys: As Sunday papers turned to colour print papers they introduced paper cut-out toys such as paper dolls and miniature stage sets. The Boston Sunday Globe also gave away miniature toy versions of their colour printing machine.

- Tours: In the 1890s, news organizations including The New Yorks World, The Chicago Herald, The Boston Globe and The Philadelphia Inquirer offered tours and installed viewing galleries above their pressrooms.

- Hot air balloon trips: In 1887, The World’s Sunday edition sent a reporter out in a hot air balloon to go from St. Louis to just outside of New York. The trip, inspired by another of Jules Verne’s novels, was designed to show readers that the newspaper could bring fiction to life.

- Comic mascots: Some of the earliest recurring cartoon characters were newspaper mascots. The Boston Sunday Globe’s “Globe man,” for example, had a torso the shape of a globe and a waistband reading: “The Largest Circulation in New England.”

Audience Engagement Now

- Virtual reality documentaries: The New York Times has a virtual reality app to showcase its VR films while other major news outlets, like The Globe and Mail, are experimenting with the new immersive technology.

- Social media apps: Most, if not all, major news outlets can be found on Instagram and Facebook, where they engage with their readers through comments. The New York Times has combined an app with celebrity by collaborating with Nigella Lawson to create a food-themed Pinterest board for Valentine’s day.

- Tours and meetups: The Chicago Tribune and other news outlets offer tours of their pressrooms and face-to-face meetups with their journalists to give readers a look into what goes on behind-the-scenes.

- Collaboration between writing and radio: The New York Times has worked with public radio WBUR to create a podcast of its weekly “Modern Love” column, and with WBEZ Chicago’s This American Life to tell a patient’s story about being shot in the chest by hospital guards.