By STEPH WECHSLER

Special to the RJRC

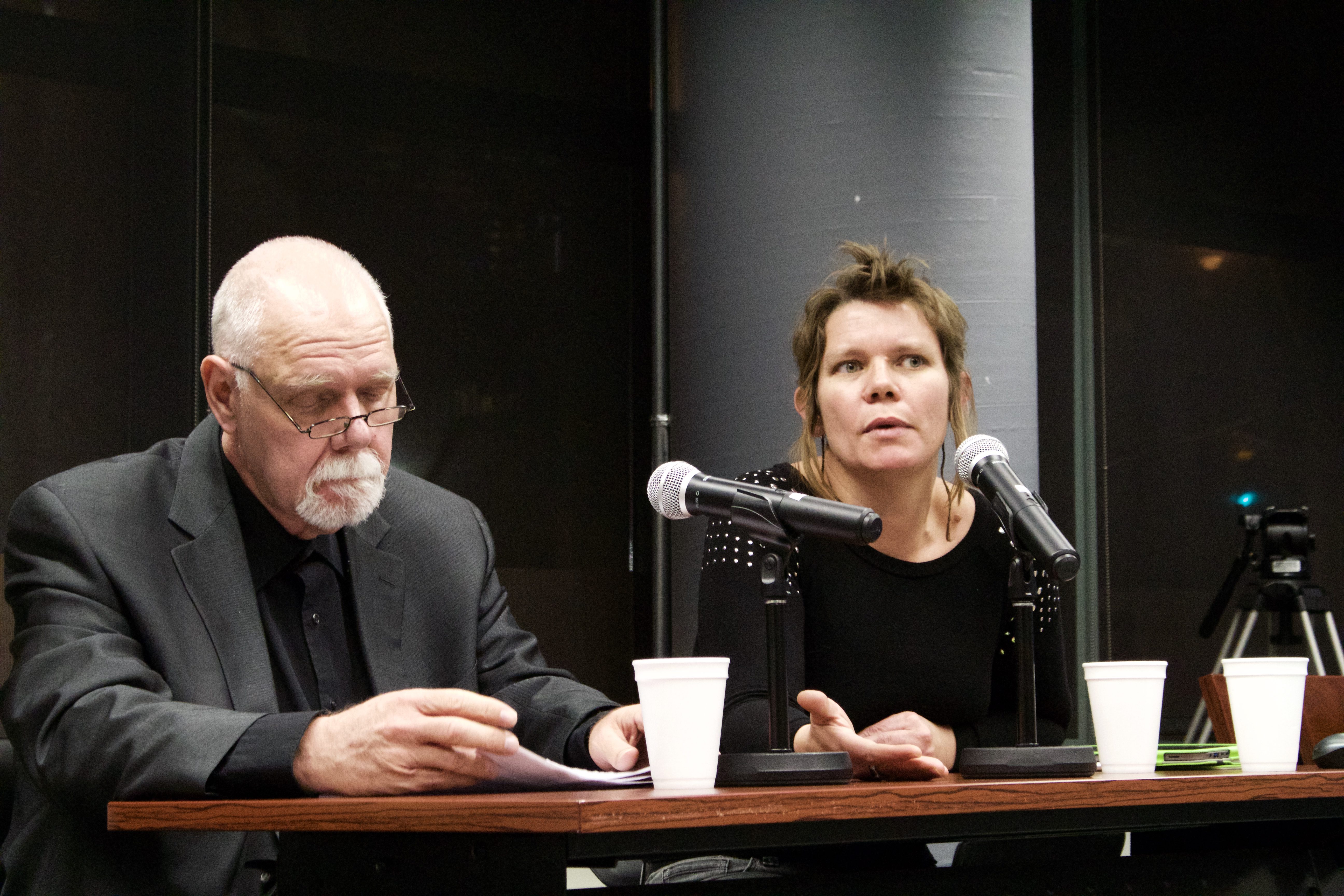

The ongoing discussion about the state of Canadian news media tends to overlook what’s happening in smaller communities, local news advocate Robert Washburn said during a recent presentation at the Ryerson School of Journalism.

Community-based newsrooms, including local television and community-run radio stations, are deeply rooted in smaller cities, towns and rural areas and reflect those places in their news coverage, said Washburn, a professor of journalism at Loyalist College in Belleville, Ont.

But much of the discussion about how to boost Canadian journalism isn’t necessarily helping support these hyperlocal outlets: “The lack of resources for these newsrooms is an abomination. The expectations are ridiculous. There’s a lack of staff, there’s poor wages, there’s unpaid overtime. Little or no training and the use of personal equipment. It goes on and on,” says Washburn. who runs Consider This, a hyperlocal news site that focuses on Northumberland County.

“I would encourage the discussion going forward to include neighborhoods, hamlets, villages, towns and small cities.”

Washburn was part of a Feb. 9 panel marking the book launch of Journalism in Crisis: Bridging Theory and Practice for Democratic Media Strategies in Canada. The book, published by University of Toronto Press, is an anthology of writing by academics, activists and other stakeholders. Edited by Errol Salamon, Christine Crowther, Mike Gasher, Colette Brin and Simon Thibault, the collection presents recommendations on public policies to bolster journalism that supports democracy. Washburn’s chapter, “Journalism on the ground in rural Ontario,” argues for promoting innovation in the community news sector, and calls for funding to be made available for journalists to develop hyperlocal sites.

Washburn characterizes hyperlocal journalism as news that serves populations of fewer than 150,000 people. The term is used more in this context in the United States and United Kingdom, but Washburn said it would be helpful in Canada and make “an important distinction in our discussions.”

On-the-ground reporting in smaller communities is essential, he said, because major news organizations don’t typically have many resources available to cover places beyond their own city limits.

“When anything happens outside of an urban area –– in a small community –– (their) only interest is if there’s a cute event like a church bazaar or the pickle festival, or when there’s a tragedy or a crisis. Reporters are often parachuted in, with little understanding of the local context. Then they disappear without going any deeper or following up,” he said.

“It’s sort of a hit and run approach.”

Gretchen King, one of the book’s co-editors and another of the panelists, said community-based newsrooms are not only ignored but put at a disadvantage by Canadian policies, including those of the federal broadcast regulator, the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission. This fall, for instance, new CRTC rules will require increased spending on local television news shows, but the money will come from funding currently allocated to community TV stations that carry local sports, community-service programs and talk shows.

King, a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Ottawa and community media advocate, works with Groundwire, a local, independent community radio program available online or on community and campus radio stations across the county. All production is volunteer-driven and collaborative, notes King in her chapter, “Groundwire: Growing Community News Journalism in Canada.”

“Groundwire not only does journalism but it defines its own journalism. We push aside the notion of objectivity and we define accuracy for the communities that we report on. So we also define that our news practices include context. Our headlines will include as much context as we can in 90 seconds. Our features do as well,” says King.

“Context is often what’s left on the cutting room floors of most newsrooms.”

Recent Groundwire programming includes:

- the “Homeless Marathon Edition,” where Groundwire explores housing-first strategies for the homeless in Medicine Hat, Alberta and how Prince George, B. C. is trying to follow suit.

- the “Canoe of Reconciliation,” which includes a story about the Algonquin people of Barriere Lake’s concerns about environmental destruction from mining on their territory.

- “Violence Against Asian Communities,” featuring discussions of sexual violence at the University of British Columbia.

- an August episode that focused on Prisoners Justice Day.

King says volunteer-run outlets like Groundwire also find it difficult to survive because audiences often don’t recognize their work as actual journalism. The assumption, she said, is that real journalism is only done by professionals. To give projects like this the opportunity to both thrive and be recognized as an essential part of the media ecosystem in Canada, she argued, people need to acknowledge that volunteer-driven urban and rural media have very different concerns and will not benefit from blanket solutions to the challenges faced by news media in general.

“It’s not just a crisis of economics, it’s a crisis of politics…If (Canadians) want a democratic, vibrant, independent, autonomous, sustainable news system that’s going to serve them the kind of news that will help them make informed political decisions, then they have to have the political will to have the policies, the politics, and the economics in place to support that news system,” King said. “We don’t have that now and we need to get organized so we can have that in the future. Where is the advocacy centre for journalism? It sounds like we need to get organized.”