By KIERAN DELAMONT

Special to the RJRC

Conventions that govern reporting on suicide — conventions that often dissuade journalists from publishing for fear of sparking copycat acts — are outdated and anachronistic, says Globe health reporter and columnist André Picard.

“[They are] especially not going to work in the brave new world of the Internet,” Picard told a group of about 30 academics, doctors and journalists at the Suicide Prevention Media Forum on Nov. 6.

“The Globe and Mail, the Toronto Star, they’re the least of your worries now. What you should be worried about is where your kids live — your kids live in cyberspace. If you want to know how to kill yourself, Dr. Google is more than happy to help.”

Picard noted that the Canadian media has done a better job of covering suicide and mental health issues in recent years: “For a long time, there was a taboo around suicide,” he said. “The fact that we’re writing about these issues much more openly is great.”

He insisted, however, that there is still plenty of room for improvement.

“We still have to work on the language a lot,” Picard said in an interview following the forum, which was organized by Toronto Public Health, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, and the Globe and Mail. Many journalists, he noted, still use ‘committed’ suicide, rather than the value-neutral ‘died by suicide’ or ‘killed herself.’

Gavin Adamson, a professor at Ryerson’s School of Journalism, agreed that media has improved when it comes to reporting on suicide. He is nonetheless still critical of the tendency to report on suicide from a crime perspective rather than as a health issue.

“Journalists spend too much time clustered around the cop desk,” he said in an interview. “I don’t think people are as interested in every little car accident or murder as we assume they are.”

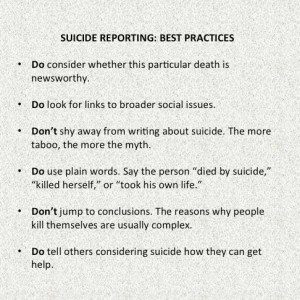

Picard was the lead author of “Mindset: Reporting on Mental Health,” a 2014 publication by the Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Trauma that offers journalists guidelines for reporting on suicides. The guide advises journalists to report only on newsworthy suicides, avoid gratuitous details and use plain language.

Picard said journalists should also be skeptical of the notion that careless reporting on suicides can lead to an increase in the suicide rate: “I actually find the notion of copycat suicides to be dubious.”

Health experts, however, disagree. Panelists Dr. Mark Sinyor, an assistant professor in University of Toronto’s psychiatry department, and Dr. Jane Pirkis, director of the Centre for Mental Health at the University of Melbourne in Australia, both insisted the ‘Werther Effect’ is real. It posits that careless representations of suicide in the media can cause copycat suicides and spark a suicide contagion.

“When there’s excessive reporting,” noted Sinyor, “you do tend to get an increase in suicides.” Reporting that highlights the method of suicide, speculates about motivation and does not include resources for others who may be suffering, argued Sinyor, can lead to a contagion effect.

He cited the 1998 case of a middle-aged woman in Hong Kong who took her own life by leaving charcoal burning in an enclosed space. After the suicide was highly publicized in the media there was an increase in charcoal-burning suicides.

Adamson, whose research investigates portrayals of mental health on social media, urged journalists to take the research supporting suicide contagion seriously: “For journalists to keep guffawing at that is absurd. There’s concrete analytical evidence there.”

Despite their differences, Picard, Sinyor and Pirkis all joined in praising Australia’s Mindframe National Media Initiative. Since 2002, the Australian Department of Health initiative has worked with journalists, journalism schools and media outlets in Australia to educate reporters on best practices for covering suicides. Mindframe’s resources include practical guidelines for reporters tasked with covering suicide.

It advises reporters to reflect on whether the event is really newsworthy. Celebrity suicides, for example, are unavoidably newsworthy, but the vast majority of suicides do not meet that newsworthiness standard. Once the decision is made to cover a story, Mindframe suggests the news should be published on the inside pages of a newspaper, or low in a broadcast lineup. It also suggests that journalists avoid gratuitous details, omit information about methods or locations and avoid using language that may cause offence, glamourize or sensationalize suicide. For example, reporters should refrain from using the phrase “successful suicide,” and should instead say “died by suicide” or “took their own life.”

“Any journalist coming out into the world of journalism in Australia these days would have been exposed to at least one lecture, probably more than one lecture on the importance of reporting on suicide well,” Pirkis said.

Similar guidelines are found in the Canadian Mindset guide. It notes that in the age of social media, false information and rumours run rampant. The authors urge journalists to engage in open discussion and use plain language in their coverage of newsworthy suicides.

The Mindset site also says stories about suicides should address the victim’s suffering in the context of broader mental health issues.

Click to enlarge

Source: “Mindset: Reporting on Mental Health” by the Canadian Journalism Forum

on Violence and Trauma, 2014.