By JASMINE BALA

Staff Reporter

The amount of news available about local contests for member of Parliament during the 2015 federal election depended on where in Canada voters were living, a new study by Ryerson University’s Local News Research Project suggests.

The research, which compared local coverage of the race for MP in eight communities in Ontario, Manitoba and British Columbia, was presented to the House of Commons Heritage Committee on Oct. 6.

“People who lived in a place like Kamloops enjoyed relative news affluence compared to, say, people who lived in a city like Brampton or a rural area like the City of Kawartha Lakes,” Ryerson School of Journalism associate professor April Lindgren told MPs on the committee.

Lindgren said that in the month prior to the election voters in the suburban community of Brampton, Ont., and the rural municipality of City of Kawartha Lakes, Ont. were among the least well-served in terms of access to news about candidates vying to represent them in Parliament.

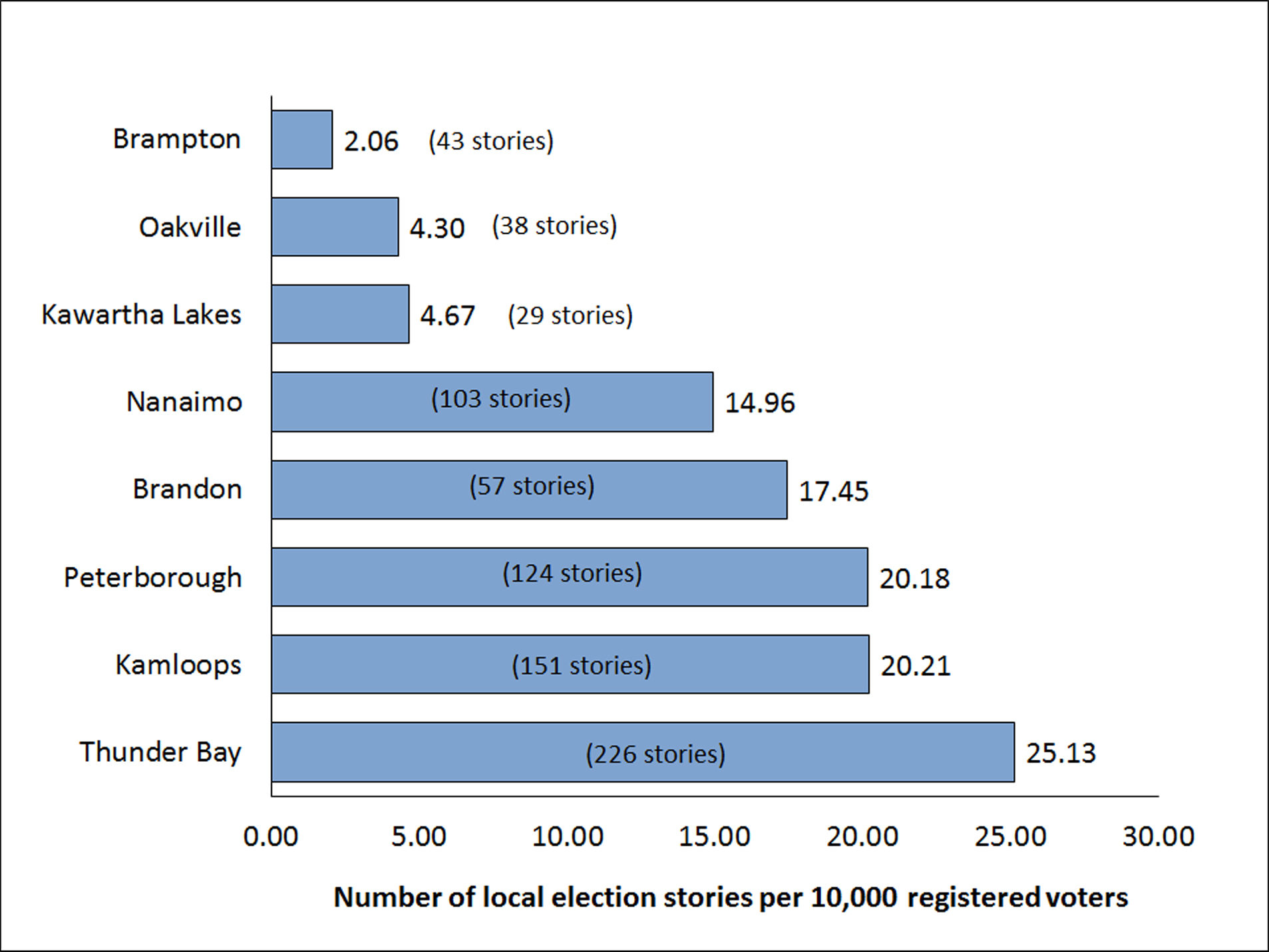

The study examined local media coverage of the contest for MP in three of Brampton’s five ridings and identified a total of only 43 election-related stories, or two for every 10,000 registered voters. In the City of Kawartha Lakes, local news producers generated only 29 stories, or 4.7 per 10,000 registered voters.

Voters in Kamloops, B.C. and Thunder Bay, Ont., by comparison, were much better served. Local media in Kamloops produced 151 stories, or 20 per 10,000 registered voters, during the month leading up to the election. In Thunder Bay, there were 226 stories, or 25 per 10,000 registered voters.

The federal heritage committee has been conducting hearings since January as part of a special study examining media and local communities. MPs are investigating the access local communities have to Canadian news and content on all platforms, including digital, and the impact of media consolidation on how Canadians are informed. Witnesses have ranged from academics and newspaper publishers to broadcast executives and officials from unions representing media workers.

“People observe or consume media in a different way now…because of the Internet. And there’s also an assumption – and this isn’t specific to any demographic – but we like it for free,” committee member and former journalist Seamus O’Regan said in an interview. “So we need money in order to pay for resources and in order to pay for strong journalistic talent. How do we square that circle? And within that environment, what’s the role of government? What [is] at our disposal to make sure that people do get the news that they rely on and that they care about?”

O’Regan, the Liberal MP for St. John’s South-Mount Pearl, said local news coverage plays an important role in communities.

“If you don’t have strong local news, you [can’t get] right down to the real nitty gritty of matters in municipal councils,” he said.

During the committee meeting, O’Regan said the Ryerson presentation was “key” as it included “very recent and empirical data,” and will be added into the committee’s final report, which is due to be completed by Christmas.

In her presentation, Lindgren said that election coverage of local races for MP is a strong indicator of the robustness of local news coverage.

“(For the purposes of the study) we were interested in election coverage because the race to represent a community in the House of Commons is a major news event that would warrant news media attention … it’s an important part of how people find out about their choices and potentially view their choices. As such, we think that in some ways it can be thought of as a proxy for the overall performance of local news media in general,” said Lindgren, who conducted the study with assistant professor Jaigris Hodson from Royal Roads University.

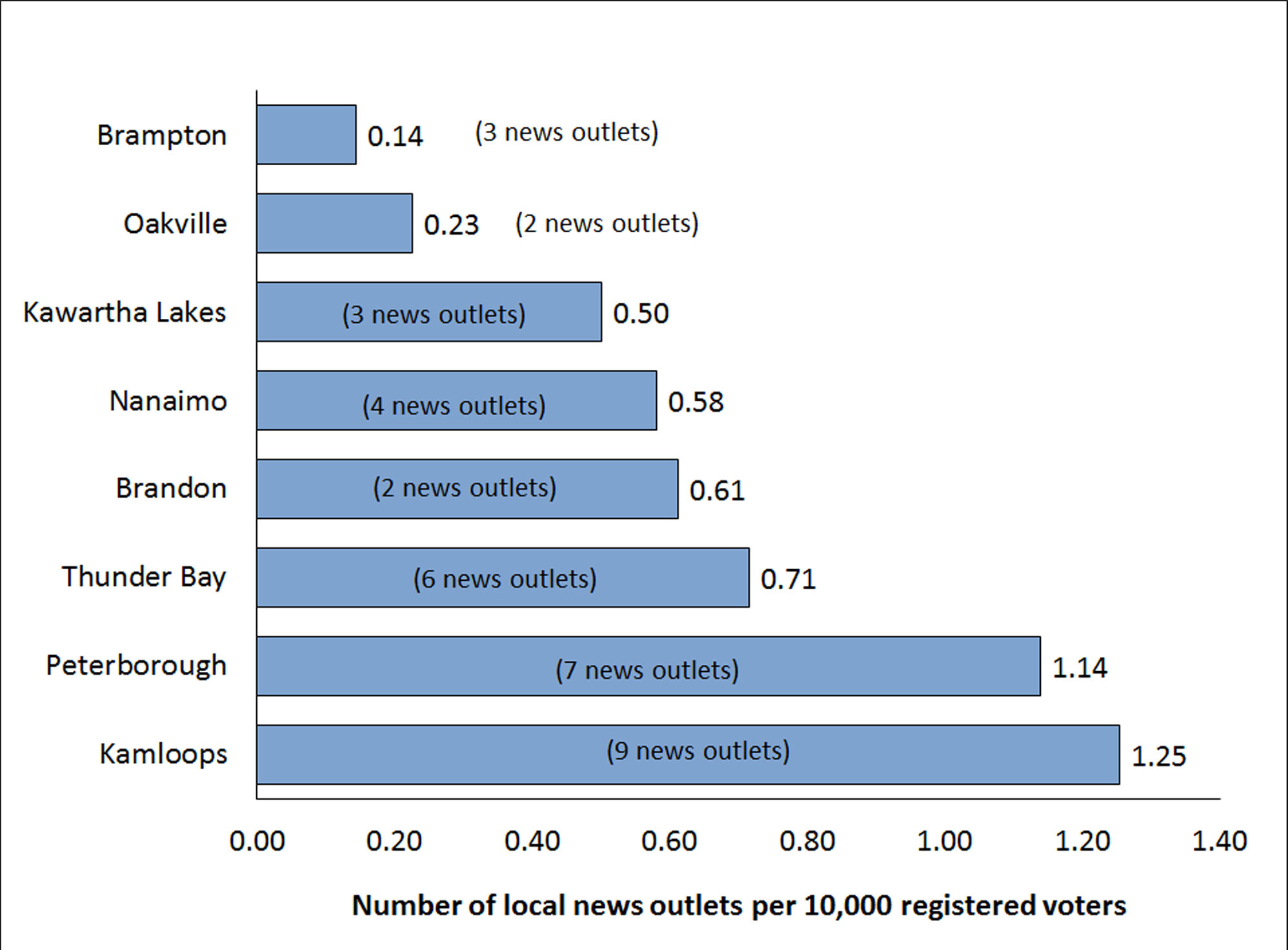

Lindgren told the committee that the research results also pointed to significant differences in the number of news sources serving different communities: The researchers identified just three news outlets – or 0.14 news organizations per 10,000 registered voters – in the Brampton ridings they examined. In Kamloops, by comparison, there were nine news outlets operating at the time of the election, or 1.25 news outlets per 10,000 registered voters.

Overall, Lindgren said, the results suggest suburban and rural municipalities are relatively underserved in terms of access to local news. The data also point to significant differences among small and medium-sized cities.

While media coverage during federal elections tends to focus on the leaders, Lindgren said reporting by local news outlets could have an impact on individual races for MP. Research suggests, she says, that the local candidate matters to up to three per cent of voters.

“That might not sound like much, but the margin of victory in 44 ridings during the last election was three percentage points or less,” she said.

Lindgren told MPs that the local news situation in two of the communities examined during the study has actually deteriorated since the federal election. The Nanaimo Daily News, which published more election-related stories than any other media outlet in that B.C. community, closed earlier this year. And on Sept. 30 newskamloops.ca, a local online site that provided some of that city’s most extensive election coverage, also ceased publication.

Lindgren said the next step in the research will be to create a local news poverty index that can be used to rank communities in terms of the relative health of their local news situation. This index will be used as the starting point to investigate why some communities are more poorly served in terms of access to local news than others, and to identify possible solutions.

In addition to the election research, the brief Lindgren presented to the MPs outlined data from the crowd-sourced Local News Map. The interactive digital map, launched on J-Source.ca in June, allows users to add information markers that record changes to local news organizations including, for instance, the launch or closure of a news source and service increases and reductions.

Three months after its launch, the markers on the map show that newsroom closures are significantly outpacing the launch of new local news sources.

About 53 per cent, or 164 of the 307 markers, on the map as of Sept. 25 documented newsroom closures, while only about 21 per cent (63) highlighted the launch of new local news outlets. The map, which is also a Local News Research Project initiative, tracks changes going back to 2008.

“The map tells a pretty powerful and disturbing … visual story of newsroom closures that far exceed the number of new ventures being launched,” Lindgren said.

Lindgren, who created The Local News Map with associate professor Jon Corbett from the University of British Columbia Okanagan, said their goal is to generate up-to-date data and spark debate about the state of local journalism in Canada.

“There’s been a major disruption in the news industry and people who live in smaller cities, towns, suburban communities and rural areas have fewer options to begin with and in recent years their choice has become even more limited,” she said.

The map, Lindgren cautioned, is only as good as the information contributors add to it. She noted, however, that it is moderated to ensure the information on it is reliable and argued that the overall trends reflect reality. She is also asking users to complete a survey on local news in their community.

Lindgren said her interest in what she calls “local news poverty” originated from an observation about the unequal access to local news in the Greater Toronto Area. Toronto residents, she noted, have access to four daily newspapers and many online television and broadcast outlets.

“[Meanwhile] a nearby city like Brampton, which is Canada’s ninth-largest city and has more than 500,000 people in it, relies pretty much exclusively on the Brampton Guardian, a Metroland Media-owned community newspaper,” she said. “There’s no local radio, no local television and no local daily newspaper that focuses exclusively on news from that community.”